Introduction

Our reason for crossing the Bosphorous was to see how the Turkish people grow tree crops, particularly chestnuts. The trip was partially inspired by this article. People in Anatolia have been tending chestnuts far longer time than the current iteration of chestnut farming in the US. Similar to our trips to Italy, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, we planned our itinerary based on a few hunches, and a lot of curiosity. The trip happened against a cultural background that included Danilo Coretllino’s Chestnut, Porcini and Rosemary Risotto recipe, Jonathan Katz’s version of Lamb and Chestnut stew, targeted ads from our friends at the amazing Perennial Crops Nursery, amusing headlines around the 2024 Conkers Controversy, and competing ideas of the best ways to cure chestnuts for flavor and nutrition. We flew into and out of Istanbul from Cincinnati.

Because some of my readers are permaculture people, I must make a comment about Turkish home gardens. We saw these in villages and cities that we passed through, including between new high rise apartment buildings, tiny cottages, and every scale in between. In full sun, people grew pole bean, hot peppers, and huge green pumpkin-esque squash with deep orange flesh. Those winter squash were thick-walled monsters. I think you can buy these under the name Adapazari a type of blue pumpkin, species Cuburbita maxima. In larger home gardens and small alley cropping settings, we saw at least several kind of collard or tree kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) being grown, sometimes several acres at a time, usually under and between walnuts. In most villages each yard has at least three fruit trees. Short fruit or hazel trees in these home gardens would usually get pruned so that the first branches would be over my head, high enough to allow more light down to the annual crops. In the yard of the Plane Tree Mosque, there were many hot peppers being grown. They had left a spruce tree growing amidst the peppers, and it too was pruned up quite high so as to successfully reduce light competition.

Specifically for my Turkish friends, I want to prelude the rest of the story with a horticultural reflection on an agricultural struggle that they’re figuring out. Türkiye’s gall wasp woes are new, and well documented. Introducing a parasitoid wasp with high host fidelity to control gall wasp impact has been proposed. Fighting monsters with monsters makes a lot of people nervous, so I suggest reading the article linked above before you make up your mind. Grafting newly developed cultivars into an existing orchard is another way to support yields despite pest pressure.. Our fruit and nut aficionado friend in Trabzon, Omer Selim, suggested the cultivar “Ertan”. I think he described Ertan as a 3:1 Sativa:Mollisima with good size, flavor, production as well as strong blight and gall wasp resistance. Here is a paper documenting the gall wasp resistance of Ertan and other promising cultivars. These are two tactics that I imagine could form the basis of an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy. Getting permission to release this second wasp, and getting access to the gall wasp resistant scionwood, are solvable problems I think. Whether or not these are desirable tactics to be deployed in Türkiye is a decision for Turkish farmers, not American farmers.

With those findings stated and cited, let’s get into the stories. The first is what I’ll call the Chestnut UBI in Bursa. Chestnut honey was a major headline. There is also the current center of Turkish chestnut production in Aydin, where we saw 30,000 acres of contiguous chestnut orchard being harvested. A lot could be said about our observations of Turkish hazelnuts, which seem to be analogous to how corn is treated by US agribusiness, but that is for another time. I will treat each topic here as separate, even though these topics are connected in many ways.

Chestnut UBI in Bursa

Everyone in-country, when hearing that we wanted to experience chestnut culture, said “Go to Bursa!” Street vendors would say this in Istanbul, as they served us charcoal-roasted chestnuts in front of every major mosque and tourist attraction. Chestnut translates to “kestane” in Turkish. There are normally annual chestnut festivals in Beydağ, Sinop and Bursa. Ultimately most of these events did not occur in 2024, though we missed one in Sinop. Bursa used to be the top-producing chestnut producing region, and is still arguably the cultural capital of chestnuts. However, we were told that a combined assault of chestnut gall wasp and blight had killed a whopping 80% of the trees in Bursa, including the famous “1000 Year Old Chestnut Tree” nearby.

Why is Bursa the chestnut cultural capital of the country? That is a *very* interesting tale involving chestnuts, religion and politics. Once upon a time, one of the Ottoman Sultans had a mosque built in the Tophane district of Bursa. It is the one now known as Kavakli Cami. An old man came and, without asking permission or receiving command, and planted a plane tree in front of the mosque. The Sultan was surprised and very pleased when he saw the plane tree growing. So, the Sultan asked his staff to find the person who planted the plane tree, and bring him in for a royal audience. The staffers dutifully found the old man who had planted the plane tree, and invited him to the palace. The old man hobbled in, leaning on his stick. The Sultan said “Grandfather, throw your stick in the air. Say aloud what your heart desires, before the stick falls to the ground. Whatever you wish, I will grant it- what do I care? I love that tree!” The old man bowed. Then, with surprising force, he threw the stick in the air and shouted “May Bursa chestnuts be a foundation!” The stick clattered to the ground. “In other words sire, I wish for everyone to eat Bursa chestnuts for free.” The Sultan agreed that from this day forth, the Ottomans would uphold this: Bursa chestnuts were free for the common folk. A foundation for the people. From that day forth, some people say Bursa’s chestnuts might be best. And the great plane tree is growing there still.

I don’t speak Turkish and the word foundation was unclear to me. I put on my “Nietzschian etymology detective hat”. Foundation is translated from the modern Turkish word “vakif”, from the Ottoman Turkish وقف (vakıf, vakf), from Arabic وَقْف (waqf). And waqf has a *very specific* meaning. Arabic-speaking and Muslim friends, chime in here. In Islam, a waqf is an endowment of land given for religious or charitable purposes. In this case the waqf is the north-facing slope of Uludağ, the ancient Mysian or Bithynian Olympus. Uludağ is the highest mountain in Türkiye, and overlooks the former Ottoman Empire capitol where we were staying. Before the yields were negatively impacted by blight and gall wasp, chestnuts were harvested for free by peasants. Some they undoubtedly ate themselves. These nuts had also been the origin of the chestnuts for Istanbul’s food cart operators. That’s an interesting food system, is it not? I have been thinking of the chestnut waqf as a “Chestnut UBI” for Bursa residents, once upon a time. So we went to Bursa to learn what more we could about this.

After buying chestnut candies in Bursa, and then later more chestnut chocolate confections in a shopping area on the way to Şirince from Bursa, we sought out the Kavaklı Cami- the Plane Tree Mosque. The plane tree that the old man planted is still alive, but it has been struck by lightning, and just a shard of the original tree was left. There were a plethora of root sprouts.

We went inside the Plane Tree Mosque, but the imam was out. By finding the Plane Tree Mosque, we confirmed that its tree was different than the Inkaya Plane Tree in the next valley over. That one is 600+ years old and supposedly the largest tree in the country. We considered visiting it, but decided instead to climb Mount Uludağ.

We went to Uludağ Milli Parkı, the national park, poking around looking for chestnuts. We found ourselves surrounded by permaculture homesteads. More of the home garden pattern was observed. This looked like people tilling the ground under orchards with walk behind tractors, which we observed directly. In an area with limited rainfall, slow weed growth and high wildfire danger, this makes more sense than in Ohio, for letting precious rain soak into the ground. We saw a fair amount of intensive vegetable and melon production with bees, chickens, goats and ducks. This was reminiscent for us of the datchas above Almaty, Kazakhstan, except unlike that place, this homestead area was obviously being expanded into, and the newer houses generally followed suit with the area’s traditional homesteading. There are many pre-fab cabin kits that are replacing the tumbled-down rock wall houses in this district… Our rental sedan could not reach the upper slopes. The gondola to the top, that skiers and hikers typically take, was down for maintenance. There were multiple roadside stands selling chestnut honey on the lower slopes, and it tasted good but obviously had wildflowers in the flavor profile as well as kestane.

Chestnut Honey

There were beekeepers with roadside stands on Uludağ. We sampled some and it was great. Because everyone always asks, chestnut honey is not honey with chestnuts floating in it! It is like clover or orange blossom honey- a single origin nectar source was used by the honeybees in the production of the honey. Bee keepers move the hives to where the flowers are blooming, for chestnut honey you move the hives into the forest or orchard while the chestnut trees are blooming. Yes, chestnuts can completely pollinate via wind, without insect pollinators. But if you get honeybees involved, you can produce honey with a distinct aroma and taste profile that has specific health benefits. You can speed-read this very interesting paper to understand why chestnut honey’s health benefits excite me. Maybe chestnut honey is better for wound healing than Manuka honey!

Şile is a town on the coast of the Black Sea, and the chestnut honey produced there is renowned. Allegedly there is also special chestnut honey vinegar produced there. We found the chestnut honey, but no chestnut honey vinegar, though we tasted generic honey vinegar. That damn magical acetic acid completely eluded us, but I assume you’d be able to taste the kestane in it. We did not get to visit Bartin, but Bartin chestnut honey is also supposed to be quite good.

Aydin

Beydağ and the surrounding area grows 76% of Türkiye’s chestnuts now, at an altitude of 600 to 1000 meters. We visited our good friends Çetin and Hüseyin Camurcu at HC Spice in Beydağ. We hope to work with them more in the future. They gave us a grand tour! They sell 4,400,000 lb of chestnuts per year out of quite a large processing facility and a contiguous mountainside chestnut growing district. Bursa used to be the chestnut capital, but no longer. It’s here.

The HC Spice facility processes bay laurel, sweet chestnut, figs and oregano. It is a humongous place. They harvest and burn the invasive English ivy from their orchard to dry their bay laurel on the branch, which we found particularly noteworthy. For many people, including myself, the notion of “invasive plant medicine” is a little bit woowoo and impractical, but viewed through an asset-based lens these folks have found an agriculture outlet for one invasive species, and this use seemed to be keeping the population in check. It sounds like most of the ivy is harvested off the trunks of the trees and the ground, on an annual basis. Is that alley cropping or forest farming?! The USDA’s schema did not prepare me for this.

We drove the valley and up into the mountains where the chestnuts grow. Some people in Türkiye referred to chestnuts as “the bread of the mountains”. In the valley we observed mostly cotton, greenhouses, landscaping horticulture, olive, pomegranate and fig. We saw cotton alley cropping between new olive orchards, multi-species orchards of walnut/olive and olive/fig. As we snaked up the steep mountainside, we entered an anthropogenic forest. It seemed like a primeval yet intensively managed orchard. I think any student of sustainable agriculture would find meditating in this type of setting to be extremely edifying, as we did. The higher we went, everything shaded into chestnut, cherry, fig and oak- majority chestnut. Up the mountain we climbed, past work gangs of people climbing the trees and beating the branches. Their counterparts on the ground were picking the ground clean, so the team could pass through the orchard in one wave and be finished with it. Other workers carried bags of chestnuts and burs away. Consistently they’d pile up the chestnuts on tarps 4 or 5 feet high, and cover in fern leaves that were harvested from the orchard floor to keep the nuts from desiccating. The piles were left for 20-25 days, we were told. Our Turkish hosts surprised us to no end with their methods. They said this in-field storage results in bigger, sweeter, uniformly ripened nuts. The bad ones mold out and are easy to discard… they put mini sprinklers on top of these piles. To compare to how we do it in Ohio, this is sort of like the step that Route 9 takes with their high humidity lettuce cooler.

We learned that they use prescribed fire in the chestnut understory. They burn the grass off in February or March. Burning off the thatch makes their Herculean task of weed whipping the orchard much easier.

The view from the mid-slope was beautiful. The town and its reservoir spread out below us. The reservoir was scarily near empty, compared to 5 years ago. Just not enough rain. I asked about mushrooms under the trees and they said yes but not many on dry years. We did see what I think were Slippery Jacks Far above were a series of bald nobs, which they tell me paraglider pilots launch from. Guess I’m coming back!

Hopefully I can bring back a bunch of chestnut flour, made to our specifications by HC Spice.

Chris noted some details in here that are worth sharing. The worker who uses a stick they pay 4000 Lira per day because it’s dangerous, you have to get up in the tree. The workers who pick on the ground get 2,000 Mira per day 8-hour days. Our hosts said maybe 500 farmers sell to the co-op. They hire many workers to bring in the harvest. I don’t yet have a clear picture about how many trees or acres each farmer manages. What’s the average farm size? I don’t know.

Conclusion

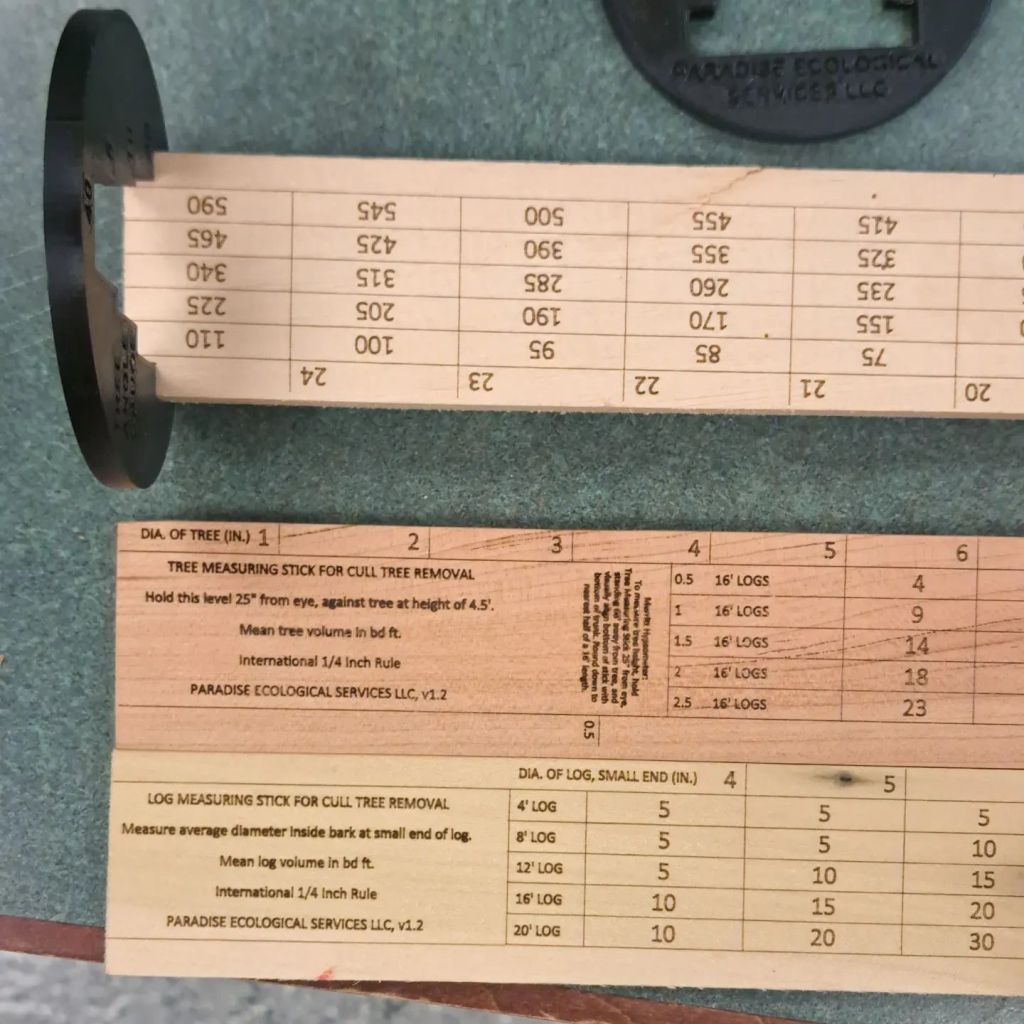

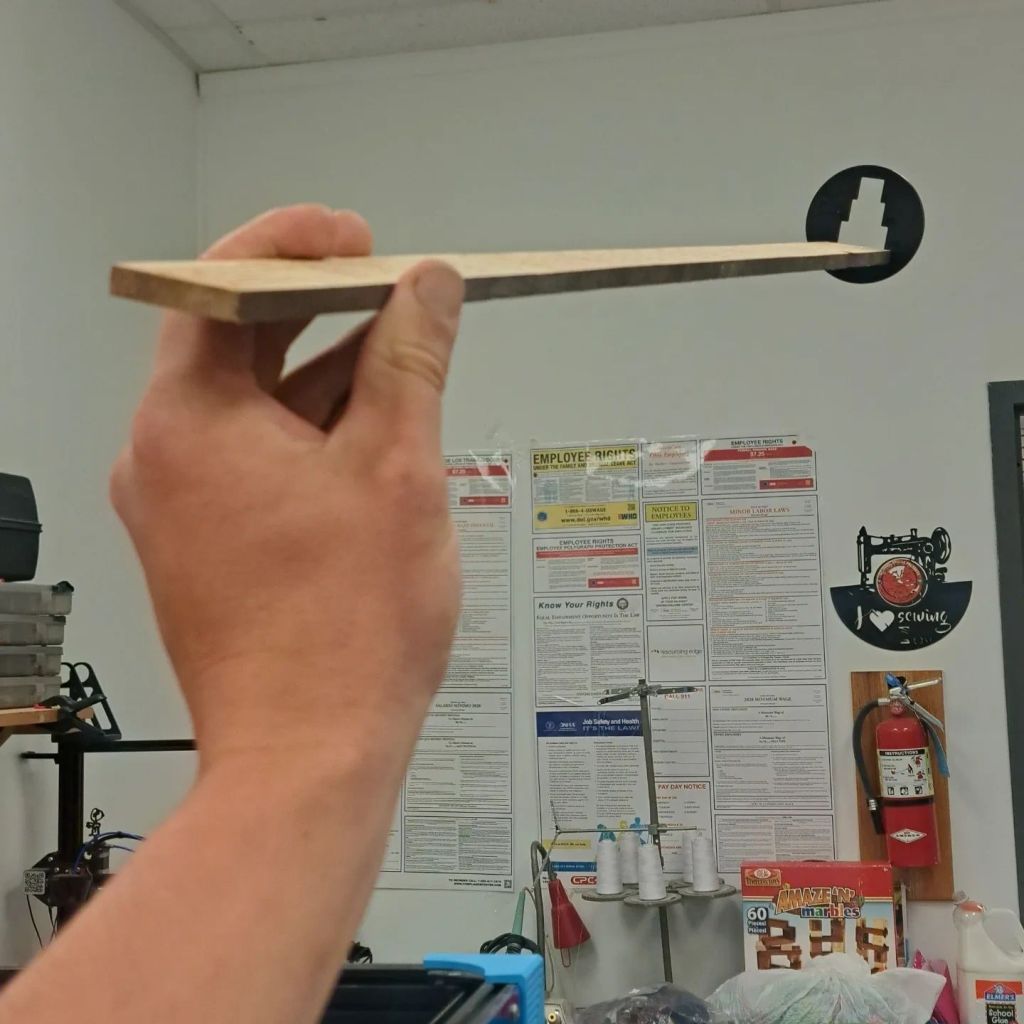

We did many things and visited many places not reported in this summary. Hopefully our permaculture friends, our friends in Türkiye, our consulting forestry clients, and our allies in the US chestnut industry will find these remarks useful. Would you like to know more? Feel free to reach out to Southern Ohio Chestnut Company or Paradise Ecological Services to discuss further.