Introduction

Supported by SARE, the Southern Ohio Chestnut Company is mid-way through our farmer-led research project. “Chinese chestnut seedling mycorrhization with porcini”. This is the second research update to the public. We had intended for this to be a quarterly research update. Our progress, dependent on fluctuating weather and mushroom fruiting cycles, has not been the quickest version imaginable. However, we have still made significant research progress. Here is a summary of what we have accomplished, and what is coming up.

For starters, our prediction that novel species pairings between Boletus and Castanea would be feasible, vis a vis what we call the Compatible Genera Generalization, appears to have been correct. That is, if one species in an EMF genus is known to pair with one species in a tree genus, then pairings of other species from those two genii will probably work, especially if the EMF species is a generalist. In Asia, the King Bolete species Boletus bainiugan associates with the Chinese chestnut species Castanea mollissima. This fact supports our hypothesis that a North American King Bolete species can also pair with C. mollissima. Dr. Dietrich shared the Compatible Genera Generalization as a postulate from the broader mycosilviculture research community.

Mother Tree Treatment

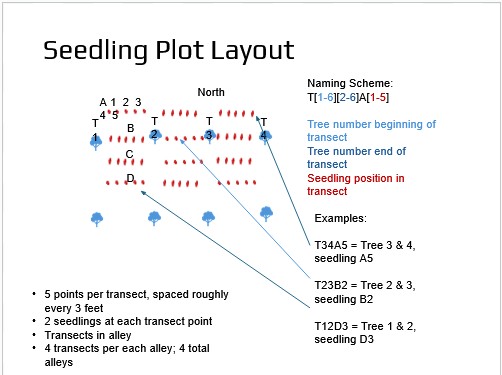

We have fully prepared to inoculate Chinese chestnut seedlings using the Mother Tree Treatment. In March, we will be planting stratified chestnuts that should be just beginning to germinate (these seeds are currently stratifying in a refrigerator in peat moss). These will be seeded two per planting site in a grid pattern, underneath a two adjacent rows of 10 chestnuts trees each (20 trees total), all of which are on a 20′ by 20′ spacing. This small area is part of a larger chestnut orchard that is completely protected by permanent metal deer fencing. This contiguous block of 20 “Mother Trees” was observed in June and October 2025 to have flushes of mushrooms growing underneath, presumably in ectomycorrhizal association with their roots. We believe those mushrooms are Boletus variipes fagicola, the Dark Brown Bolete, one of the tasty porcini species identified in the infographic shared on porcini species in Ohio. In this same site, the Cooper Orchard, other mushroom species that have been observed fruiting are what we believe to be Amanita muscaria guessowii, American Yellow Fly Agaric, and Baorangia bicolor, Two-Colored Bolete.

The June flush of Boletus variipes fagicola was larger than the October flush, by a long shot. The size of the flushes appeared to be linked to the weather. In 2025 leading up to early June, Carroll County Ohio had enjoyed steady precipitation levels of 1″ to 2″ per week. Later, a summertime drought meant we were surprised there was any porcinis at all in October.

Steps we have taken to prepare for the Mother Tree Treatment:

-We have signed an MOU with the owners of the mother tree treatment site/Cooper Orchard. Stephanie and Carl Cooper are the orchard owners and are members of the chestnut growing Route 9 Cooperative.

-We have purchased “milk carton” style tree tubes, from SpecTrellissing, to protect the seedling chestnuts in this planting from rabbit damage. Because of the deer fence, and because of the deer fence around the site where these seedlings will be transplanted in an open field for further study, temporary rabbit protection was all that we thought was warranted.

-We have developed a planting layout for seedlings in the Mother Tree Treatment. We will be planting two freshly germinated nuts per planting space in March. At first each milk carton will be labeled. After the seeds sprout, we will return in June to label all seedlings individually, for redundancy.

-We have submitted a sample of the October flush of mushrooms from the Cooper Orchard to Mycota Lab. The goal in working with Mycota is to use their inexpensive, high-throughput DNA barcoding program to get these mushrooms genotyped, and thus have the species identity of our Chinese chestnut-compatible Boletus genetically confirmed. Why is this important? Well, we want to be sure, for a plethora of reasons. Since many of the different species of Boletus have been revealed by genotyping to be sold, purchased and eaten under the false pretense of being B. edulis, we want to have transparent, honest, verified labeling of our porcini product in the future. “Eat Your Local Porcini” might become our marketing slogan. Additionally, since none of us have been to China and seen the Boletus bainiugan growing under Chinese chestnut in Yunnan, it could be possible that this somehow traveled with the Chinese chestnut here, and it would be good to rule that out. B. bainiugan is quite commonly sold under the name of Boletus edulis in the spice trade.

Mycota Lab deserves a plug for their assistance on this project, and really for their work in general. They are facilitating an amazing amount of citizen science, through the Continental Mycoblitz project. If you want to have a mushroom identified and genotyped, participation is easy. Read more about it on their website, but basically you make an observation of the mushroom on iNaturalist, you dry a sample of the mushroom, and then you print the specimen labels (including the iNaturalist ID number of your observation), and the team at Mycota will take it from there. See their website for details! Below is a picture of the mushroom we sent in from the October 2025 flush, a little over the hill but hopefully still usable for sequencing.

Liquid Mycelial Culture

Mycota also received one of our slow-to-colonize Petri dishes from the June fruiting. Truly, the mycelium has grown tortuously slow on Even though We think both of those will come back from the lab, confirming it was the same porcini species growing under the Castanea mollissima trees for both fruitings, namely, Boletus variipes fagicola. While this is not the type species of the genus, it is sold commercially to high-end restaurants and used interchangeably with Boletus edulis. There is no doubt in anyone’s mind that B. variipes is native to Ohio, unlike B. edulis, which as far as we’ve been able to determine has not been seen confirmed as growing in association with any native or Chinese hardwood trees in Ohio. We are happy to be using a native species of mushroom for this project. However, the liquid mycelial culture we are seeking to produce for this experiment is looking less promising than we might have hoped. Thomas says that the literature did report the mycelium can be quite slow to grow on plates, and our experience bares this out. The mycelium from the June fruiting is growing slower than anything Thomas has attempted to grow before, including Tuber canaliculatum, a native truffle species which some people are excited for as a candidate mycosilviculture crop.

We’re not sure that the liquid mycelial culture couldn’t still work, but we may need to go back to the drawing board in terms of the nutrient recipe. Also, picking the porcini when it’s still in the dense, early button stage, before any worms or discoloration or bacterial composition sets in, seems like a crucial step to ensuring the purity of the strain. Thomas thinks there may be contamination on his June plates, though he has employed various procedures to clean up the plates of suspected unwanted mold, with some success.

Spore Solution Treatment

Perhaps our biggest gaff in the project so far was that the large flush of mushrooms in June, which we had intended to use in the spore solution treatment on chestnut seedlings grown in autoclaved soil, was eaten before the pickers realized we needed the whole batch, and not just a sample to send to Thomas at MidAm Mushrooms and Stephen at Mycota Lab. There was some confusion with the autoclaved soil being fully of weedy seeds about a rational next step, as we had intended to introduce the spores as to chestnut seedlings growing in demonstrably sterile potting medium, which it turned out we just didn’t have access to without a steam wagon (large-batch sterilizer, sometimes used in fish canneries). To prevent the mushrooms from going bad, Amy decided to freeze the large haul of mushrooms for later use. Dietrich pointed out that freezing the mushrooms almost certainly would have adversely effected the viability of the spores from those mushrooms, much to our chagrin. Thus Amy ended up sharing those mushrooms as a feast with the Route 9 Cooperative members. That is to say, for the first time, Ohio’s chestnut farmers as a community had an ad hoc culinary experience with the porcini that were harvested from beneath their very own trees. The good news from this is they were reportedly delicious, and furthermore the Boletus variipes fagicola were indistinguishable from Boletus edulis strico sensu. Additionally, none of the porcini taste testers noticed any adverse gastrointestinal effects or other negative symptoms from consuming the stir-fried mushrooms. While Ohio Mushroom Society newsletters have shared Boletus recipes in the past, it is helpful to get confirmation of the delectability and inoffensiveness of our candidate native porcini crop species. Below is an image of the stir-fried B. variipes fagicola from the Cooper Orchard.

Conclusion

We will continue to strive towards comparing the three inoculation methods (mother tree treatment, liquid mycelial culture treatment, spore solution treatment). At this point, the liquid mycelial culture treatment would benefit from starting with a fresh button-stage mushroom from the Cooper Orchard, to reduce the chances of contamination. This would also give Thomas more chances to test for different growing medium which the B. variipes fagicola could colonize more expeditiously. Meanwhile the liquid mycelial culture treatment is also dependent on another flush of mushrooms from the Cooper Orchard. This time, the same day that the flush is observed, Badger will take the mushrooms to Cincinnati, and use them to apply a spore slurry to several air pruning beds full of Castanea mollissima seedlings that we have growing already. While the growing medium their in was never autoclaved, it was in pure pine bark fines with some minimal fertilization that should have washed out or been absorbed, entirely, by this point. We believe this low nutrient, acidic environment can be a reasonable environment for the spore solution to take hold. All treatments will be followed up with testing the seedling root tips for the presence of living Boletus variipes fagicola mycelium. We’d like to thank North Central SARE for their support of this project.

Post Script (2025.01.29)

After sharing this research update in the Facebook group Chestnuts as a food crop – Castanea species nut trees, we heard a few interesting things that are related to chestnuts and mycoforestry. Namely, Stubby Brittlegill/Lobster Mushroom, as well as Truffle species, have indicator plant species that have been found growing abundantly in chestnut orchards. This co-occurrance of understory plant with culinary mushroom is similar to how moss on the soil surface seems to be a prerequisite to finding King Bolete mushrooms nearby. This is turning into a useful body of lore. It seems like this should be written down somewhere, so I am taking note of it here for later consideration.

-It was reported that in Vermont, there is a non-native orchid species that has been found growing beneath chestnut trees. A botanist identified the orchid as Epipactis helleborine, broad-leaved helleborine. This species of orchid is dependent on mycorrhizal fungi. Of interest to mycoforestry, broad-leaved helleborine has been identified as a significant indicator species for truffle mycelium (Tuber sp.) living underground. When you pair that fact with recent research on multi-cropping edible truffles (a genus of many different gourmet culinary species) with chestnut trees., it begs the question if this non-native orchid might be pointing to truffles growing spontaneously in existing chestnut orchards.

-Another strange plant growing abundantly in some chestnut orchards, that may have a connection to future mycoforestry research, is Ghost Pipe, Monotropa uniflora. Ghost Pipe has been reported in that group to grow abundantly in some chestnut orchards in Pennsylvania. Ghost Pipe is a non-photosynthetic plant, a mycoheterotroph that gets its energy from the ectomycorrhizal fungal species known as the short-stemmed russula or stubby brittlegill, Russula brevipes. It is known that stubby brittlegill is edible, and while initially it has a bland or bitter flavor, these mushrooms “become more palatable once parasitized by the ascomycete fungus Hypomyces lactifluorum, a bright orange mold that covers the fruit body and transforms them into lobster mushrooms.” I have eaten lobster mushrooms, these are delicious. So Ghost Pipe growing in a chestnut orchard would seem to point to the presence of palatable species of ectomycorrhizal fungi. It should be noted that extracts of Ghost Pipe are being used by contemporary herbalists as a folk remedy, taken for relieving pain, grief and anxiety.